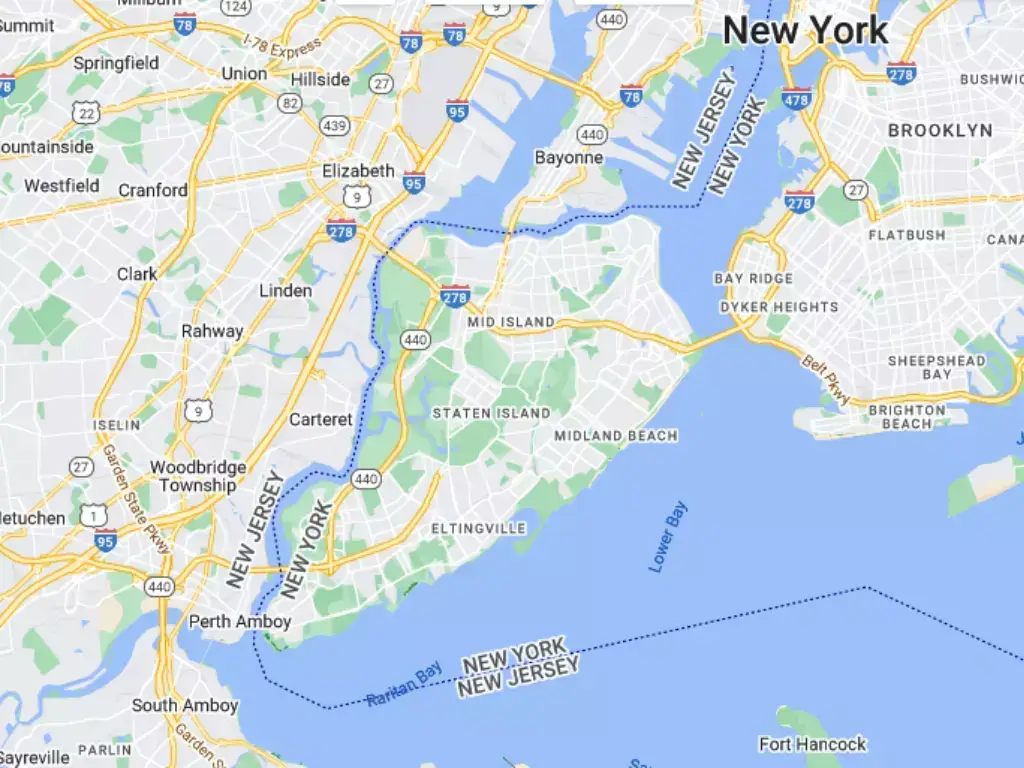

Why is Staten Island part of New York, even though it is closer to New Jersey and separated from the rest of New York by two waterways, the Arthur Kill and the Kill Van Kull? This is a question that many people ask, and the answer has to do with the history of colonialism, warfare, and diplomacy that shaped the region. Let’s dive in!

The Dutch Era

The story begins with the Dutch, who were the first Europeans to colonize the area in the 17th century. The Dutch claimed a large territory that stretched from the Connecticut River to the Delaware River, encompassing present-day New York, New Jersey, and parts of Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. This territory was called New Netherland, and it was governed by the Dutch West India Company from New Amsterdam, located at the southern tip of Manhattan.

The Dutch named Staten Island in honor of the Staten-Generaal, the parliament of the Netherlands. The island was inhabited by the Lenape, a Native American tribe that also lived in New Jersey and other parts of the region. The Dutch established a trading post on Staten Island in 1630 and bought the island from the Lenape in 1636 for 10 boxes of shirts, 10 ells of red cloth, 30 pounds of powder, 30 pairs of socks, two pieces of duffel, some awls, ten muskets, 30 kettles, 25 adzes, ten bars of lead, 50 axes and some knives.

The Dutch settlement on Staten Island was not very successful, as it faced frequent attacks from the Lenape and other Native American tribes, as well as from rival European powers such as the English and the French. The island was also vulnerable to natural disasters such as hurricanes and floods. The population of Staten Island remained low throughout the Dutch era, and most of the island was used for farming and grazing.

The English Conquest

In 1664, an English fleet sailed into New York Harbor and captured New Amsterdam without a fight. King Charles II of England granted the colony to his brother James, the Duke of York, who renamed it after himself. The Duke of York also claimed all of New Netherland, including Staten Island and New Jersey.

However, the Duke of York had a problem: he had already given away part of his land to two of his friends, Sir George Carteret and John Berkeley. In 1664, before he knew he would inherit New Netherland from his brother, he had granted them a large tract of land between the Hudson and Delaware rivers, which they named New Jersey after Carteret’s ancestral home. The Duke of York did not want to take back his gift, but he also did not want to lose control over Staten Island and other strategic locations.

To solve this dilemma, the Duke of York made a deal with Carteret and Berkeley: he would let them keep most of New Jersey, but he would retain some parts of it for himself. These parts included Staten Island, Long Island, and several other islands in New York Harbor and the Hudson River. He also kept a narrow strip of land on the west bank of the Hudson River opposite Manhattan, which became known as Bergen County.

The Duke of York’s New Jersey division was unclear or precise. He did not draw any maps or boundaries; he only described his lands in vague terms such as “small islands” or “lands lying westward”. This created confusion and conflict between New York and New Jersey over who owned what. One of these disputed areas was Staten Island.

The Boat Race Myth

There is a popular legend that says that the Duke of York decided to settle the argument over Staten Island with an unusual proposition: any small island that could be circumnavigated in less than 24 hours would belong to New York. He then hired a British naval captain named Christopher Billopp to sail around Staten Island and prove that it was small enough to be part of New York. Billopp allegedly accomplished this feat in just 23 hours, making Staten Island part of New York.

This story is widely repeated in books, websites, and even official documents. However, there is no evidence that it ever happened. There is no record of anyone telling this story until 1873, more than 200 years after the supposed boat race took place.

There is also no record of anyone named Christopher Billopp living in or visiting New York at that time. Moreover, the story does not make sense: why would the Duke of York use such an arbitrary and unreliable method to determine ownership? Why would he risk losing Staten Island if Billopp failed or cheated? And why would Carteret and Berkeley agree to such a gamble?

The boat race story is most likely a myth that was invented by later generations to explain the oddity of Staten Island’s affiliation with New York. It is a colorful and entertaining tale, but it is not true. A 1948 scholarly essay by Roswell S. Coles of the Staten Island Institute of Arts and Sciences found “no real evidence to assume there is any truth in the circumnavigation story”.

The Real Reason Why is Staten Island a Part of New York

The real reason why Staten Island is part of New York is much more mundane and complicated. It has to do with the political and military events that took place in the late 17th and early 18th centuries when New York and New Jersey were still colonies of England.

In 1673, the Dutch briefly recaptured New York from the English during the Third Anglo-Dutch War. They renamed it New Orange and reasserted their claim over all of New Netherland, including Staten Island and New Jersey. However, the war ended in 1674 with the Treaty of Westminster, which returned New York to the English. The treaty also confirmed the Duke of York’s division of New Jersey, but it did not specify the exact boundaries or names of the islands that he kept for himself.

This ambiguity led to more disputes between New York and New Jersey over Staten Island and other areas. Both colonies tried to assert their authority and collect taxes from the residents of the island. The islanders themselves were divided in their loyalty: some preferred to be part of New York, while others favored New Jersey. The situation was further complicated by the fact that the Duke of York became King James II of England in 1685, and then was overthrown by William of Orange in 1688 during the Glorious Revolution.

In 1689, a group of Staten Islanders who supported William of Orange rebelled against the governor of New York, who was loyal to James II. They declared themselves to be part of East Jersey, one of the two provinces that New Jersey had been divided into in 1676. They also asked for protection from the governor of East Jersey, who agreed to help them. However, this move was not recognized by the governor of New York, who sent troops to suppress the rebellion. The conflict lasted for several months until a truce was reached in 1690.

The truce did not resolve the issue of Staten Island’s status; it only postponed it. For the next 140 years, New York and New Jersey continued to argue and fight over Staten Island and other border areas. They appealed to the British government and the courts for a final decision, but none was forthcoming. The matter was complicated by the fact that both colonies had different charters and laws and that both had changed hands several times among different proprietors and governors.

Finally, in 1830, after both colonies had become states of the United States, they agreed to submit their case to a panel of arbitrators appointed by Congress. The panel consisted of three Supreme Court justices: John McLean, Henry Baldwin, and Smith Thompson. They examined all the evidence and arguments presented by both sides and issued their verdict in 1833. They ruled that Staten Island belonged to New York, based on the original grant from King Charles II to his brother James, the Duke of York, in 1664. They also ruled that Bergen County belonged to New Jersey, based on a later grant from James to Carteret and Berkeley in 1665.

The arbitration award settled the long-standing dispute between New York and New Jersey over Staten Island and other border areas. It also confirmed Staten Island’s status as part of New York City, which had been consolidated in 1898 with the merger of Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, Bronx, and Staten Island into one municipality.

The Twist Ending

However, there is a twist ending to this story: in 1998, more than 160 years after the arbitration award, it was discovered that there was a mistake in the map that was used by the arbitrators to determine the boundary between New York and New Jersey. The map showed a small island called Shooters Island in Newark Bay as being part of New York, when in fact it was part of New Jersey according to historical records. This error meant that New Jersey had been deprived of about 30 acres of land for almost two centuries.

The mistake was revealed by a surveyor named Mark Anderson, who was hired by Exxon Mobil to map out its property on Shooters Island. He noticed that the island was marked as part of New York on some maps and as part of New Jersey on others. He investigated further and found out that the island had been mistakenly assigned to New York by the arbitrators in 1833.

Anderson reported his findings to both states, who agreed to correct the error and transfer Shooters Island from New York to New Jersey. The transfer was approved by Congress and signed by President Bill Clinton in 1998. It was one of the rare cases where a state voluntarily gave up land to another state without any compensation or dispute.

Shooters Island is now officially part of Bayonne, New Jersey. It is mostly uninhabited and used as a bird sanctuary. It is also a reminder that history is not always accurate or final and that sometimes it can be revised or corrected by discoveries or evidence.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Staten Island’s incorporation into New York City in 1898, following the consolidation referendum, was a decision influenced by a combination of economic, political, and infrastructural considerations. The island’s strategic location, the development of transportation networks, and the desire for enhanced municipal services played pivotal roles in shaping this historic transition. Understanding this process provides insight into Staten Island’s unique identity within the broader context of New York City, highlighting the island’s integral role in the city’s evolution and the dynamic interplay of local and regional interests that continue to shape its development.